Nearly seven million people in Colombia have been internally displaced. For five decades, Colombia has faced one of the world’s most severe internal displacement situations caused by conflict and violence. Economic inequality, corruption and unequal distribution of land and resources led to a 50 year long conflict involving government security forces, left-wing guerrillas like theFARC and the ELN, right-wing paramilitary groups and organized crime rings like the BACRIM. During the conflict, non-state armed actors were especially active in marginalized areas where state presence was weak or absent. It is estimated that more than 4.5 million hectares of land were abandoned or seized during the conflict.

Even though a peace agreement was signed in 2016 between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), internal displacement in the country continues as other illegal groups remain active : in 2017 another 140.000 new displacements due to conflict and violence were recorded.

In addition, the government promotes large-scale land acquisitions policies for large-scale development projects, adding to the complexity of displacement in the country. The past government of Manuel Santos sold licenses enabling foreign companies to exploit vast amounts of native land. For instance, the Páramo of Santurbàn, … , was sold to an Emirati Mining venture – and a Canadian timber harvesting company has now sovereignty over the rain forest on the Pacific Coast.

Only around 450.000 of those internally displaced have returned home with the assistance of the government. The process of land restitution, when it exists, is extremely slow. Many of the displaced belong to Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples - their land is often located in rural, resource-rich areas that are targeted by armed groups. Minorities face particular difficulties in securing the recognition of their land rights.

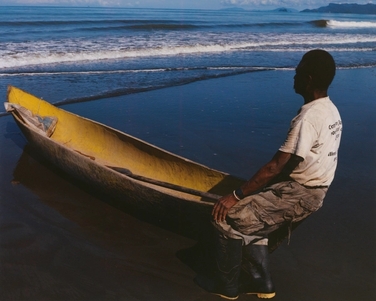

The phenomenon of forced displacement in rural zones rich in resources is throughout this series of photographs, taken during a five month long travel through Colombia’s diverse regions.

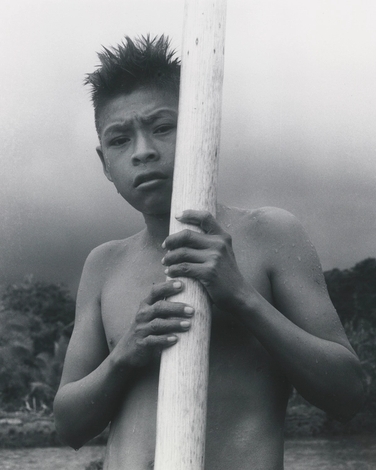

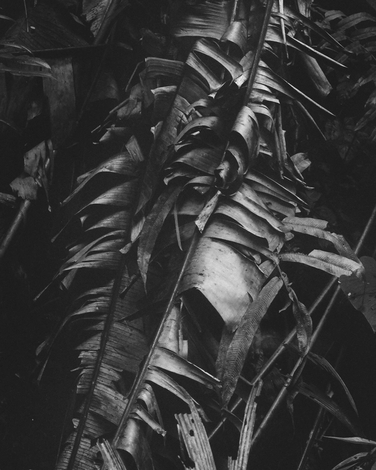

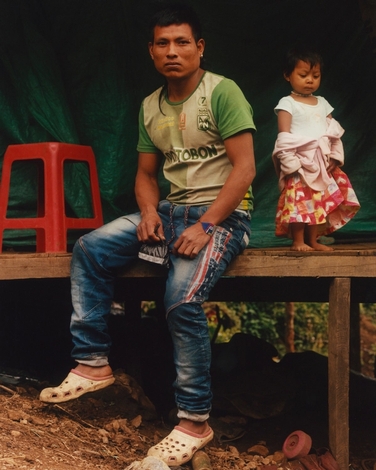

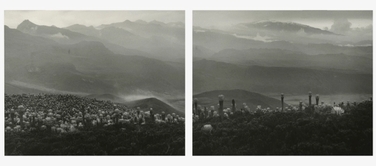

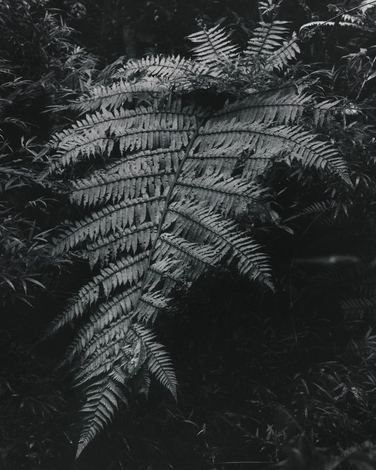

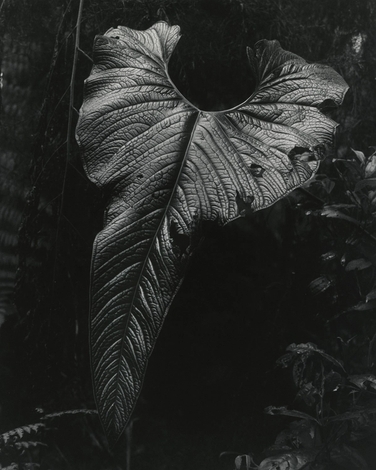

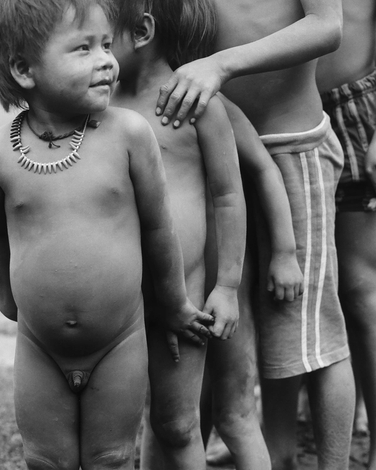

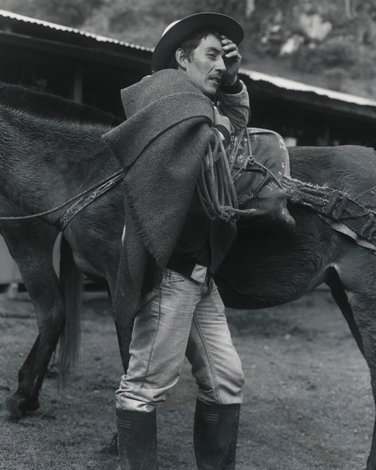

I chose to juxtapose portraits of people who suffered eviction from their natural habitat, with landscapes and plants from their native land. Thereby I hope to convey an understanding for the importance of nature for these communities and their perception of environment. My intention is to emphasize the link between people and their native land and how the disruption of this harmony has a reciprocal harmful effect.

Colombia, with three great branches of the Andes fanning out northward toward the wide Caribbean coastal plain, its rich valleys of the Cauca and the Magdalena rivers, the desert of the Guajira Alta, the many tropical glaciers, and the endless forests of the Chocóand Amazonas, is ecologically and geographically the most diverse nation on earth.

This unparalleled biodiversity is a central pillar in all of the cultures and forms social existence I encountered along the way. Indigenous tribes understand their environment as a sacred geography, approaching it with respect and rituals. In return, nature nurtures them: it is the center of life, belief and custom.

Once ties and unison with the native environment are interrupted, the human finds himself estranged and lost. The forced change of environment and living conditions are experienced as an expulsion not only from one’s territory, but from one’s lineage and identity.

What impact displacement has on people is a question that is applied here to the story of Colombia, but in general remains an important one to ask. At the end of 2017, the world hit a record high of 68.5 million of forcefully displaced people.

About a third of all people displaced by conflict in Colombia live in departments along the Pacific Coast, including Valle de Cauca, Narino, Antioquia, Cauca and Chocó.

The Chocó, one of the richest provinces in Colombia in terms of biodiversity, natural resources and precious metals, remains economically speaking, however, the poorest in the country. Before the Spanish invasion, the land was inhabited by several indigenous groups who lived in circular settlements along the three main rivers of the Chocó. When the colonizers arrived, many of the Embera people fled to the Darian jungle in Panama. Today, indigenous communities make up just 12.7 percent of Chocó’s population. After the Spanish discovered the extent of natural resources in the region, they took up to 7 thousand slaves from Africa and brought them to Choco from 1700 to 1800. The presence of African-Colombians had the indigenous communities move up the rivers and install themselves close to cities, in order to survive.

During the peace referendum in 2016, the Choco, one of the provinces hardest hit by the conflict, 80 % of the voters backened the deal.

Santa Isabel is home to a small community of Emberas, an indigenous group that has been displaced from its native land, the Chocó, from a tropical, humid climate of the Pacific Coast, to the cold mountains of Antioquia. They fled the presence of armed groups that continue to control the region of the Chocó, used for drug trade routes and illegal extractive practices, including mining and logging. In Santa Isabel, a territory solely accessible by an 8 hour foot march, situated on a mountain slope that is prone to landslides, the small community finds itself not only without sufficient nutrition, medical help and sufficient housing, but also without value and occupation. The harvest in this cold climate is completely different, other communities live far away and the old customs and habits can no longer be pursued.

Karmata Rua, an indigenous community next to the very “believer” village of Jardin, was renamed “Christiania” during Christian missions and the Spanish Conquest in Colombia, which endured from 1500 to 1810. Today the people of Christiania live a very “civilized” life, in close commercial connections with the neighboring villages, trading coffee and plantains. A catholic run college has replaced the education of children in form of stories, ceremonies and rituals. Traditional medicine and healers have been replaced by a pharmacy and a church replaced the ancestral spiritual house, the Maloca. Many scientists, language scholars and reporters had come to their village, exploring, observing and studying their language, to then leave with the information. They themselves struggle to preserve their heritage, history and culture, as they are no written accounts. The knowledge, that was for generations transmitted by word of mouth, risks to fade as the elder generation become fewer and fewer.

- Direction: Théo De Gueltzl

- Words: Sophie Strobele